You are a recent art graduate, yet despite your young age you have achieved acclaim with your highly original conceptual works which have been exhibited around Finland and at Galerie Forsblom last year. You have also won art awards both in Finland and abroad.Your most recent works are brass plates oxidized by the decomposing corpses of raccoon dogs, cattle and horses.

1. How did you come up with this technique and what does your process mean to you?

At some point I grew tired of figurative representation. Instead I wanted to create art that doesn’t represent anything, but simply is itself.

Years ago, when I hosted an open house at my studio, a visitor started touching one of my brass-plate collages. The fingerprints left on the metal surface never went away. Traces of presence thus became a theme in my work in 2014. My wife was then away and I was living alone in the middle of the forest. I slept on a brass plate, leaving a trace of my lonely presence. Shortly afterwards I took up the theme of ‘vanishing presence’ and started using death as my material.

Art also happens in-between the artworks you actually see. Of course it resides in the work itself, but the very word ‘artwork’ implies an action taken by someone before the work came into being. I regard the process as an integral part of my identity.

2. As the corpse decomposes, it imprints an image on the brass plate. How big a part do you play in the composition, or is the outcome pure chance?

Everything is pure chance and yet part of an utterly deterministic plan.

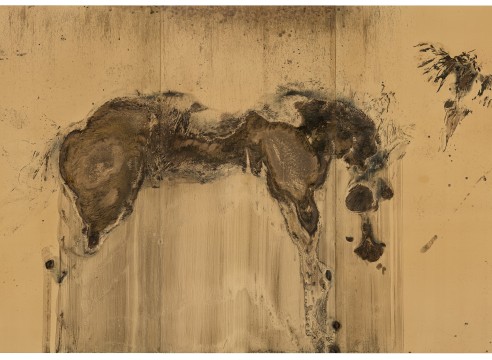

In my earlier works, I simply wanted to preserve a trace of a final moment. The result – the outline of a dead animal on a brass plate slightly larger than itself – is like a final interment. My actions are more visible in my most recent de-compositions. Still life is presented in a greater variety of forms; I have tried to limit myself as little as possible. The plates suggest many things that fall between presence and disappearance, such as birth, martyrdom, the parent-child relationship and ruptures. I have an initial idea of what I want to say and how the process should unfold, but the animal also has its say.

3. Working with death seems rough from a physical and sensory viewpoint. Yet the traces on the brass are aesthetically appealing – they have value. Which is more important to you: the conceptual or the visual?

The conceptual and the visual could be separated, but I see them as two sides of the same thing, both residing in each other. The visual side has to make an impact, whether the effect is jarring, harmonious, red, or whatever, as long it makes you stop and listen, halting you in your tracks. This, if you will, is the work’s first visual task. Then the conceptual subtext should awaken questions in the viewer’s mind.

In other words, the visual and the conceptual are equally important: visuality without conceptuality is handicrafts; conceptuality without visuality is invisible and voiceless.

4. You mentioned that your key theme is presence. What kind of presence do you mean?

There are many interwoven themes and perspectives in my work; presence is only one of them. My works also visualize how there are many different types of presence. A cow appears is one of my latest works. It does not portray the cow; rather the cow and its death are present in the work. While we are alive we accumulate energy within us, and that energy dissipates when we die: the chemistry of death – fats, salts, time, space and thermal energy – is imprinted on the metal, leading a new life on its surface. Presence can also be manifest as absence or as actions in the artistic process.

5. The memento mori is a widely cited theme in art history. What kind of existential contemplations are associated with your treatment of death?

During the 12 months I worked on my exhibition at Galerie Forsblom in 2015 I saw death nearly every day. My first child was born when we were hanging the exhibition. With the birth of my child, I realized that I had really been processing the theme of life more than death. Without death, there is no life, just as there is no light without shadow. Consider the Baroque era, a time of famine, cannibalism, plague and killings, yet people lived wantonly, with a huge appetite for life. The vertical canvas of the resurrection tumbled into horizontal position, onto secular soil. I interpret the depicted as an earthly gateway to the Hereafter (vanitas). We look death in the face in order to appreciate that I, the viewer, am alive.

At the moment of death, a completely different I reveals itself. It is not I who am but I who dies.

6. Your next solo exhibition is in the fall of 2016. What can we expect – do you have anything new in store?

I am working with a variety of materials, yet my works all address more or less the same themes. I am working with techniques that I haven’t exhibited before, but I’m not quite ready to give up my decompositions yet. This process related to the final presence is deeply rooted in me now; it has changed my whole view of art. Lately it has started revealing new sides to itself. Now I am focusing more clearly on the action itself, or the real event that is preserved as a kind of relic in the work. I want to get closer to the moment of artistic creation as I understand it.

I also work three-dimensionally and temporally. I am interested in presenting works that are in the process of unfolding. By this I mean foregrounding the documentation process and presenting ephemeral, time-specific works that visualize their future death, emphasizing their own transience and impermanence. I won’t know what kind of works I will be showing at Galerie Forsblom until I have analyzed various interwoven processes.

I personally hope to see works of greater depth, complexity and courage to break their own rules, even a bit of craziness: an equation to which there is no solution.

Toni R. Toivonen (b.1987) graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in 2016. His new works will debut at Galerie Forsblom in October 2016.